- Home

- Daniel Shand

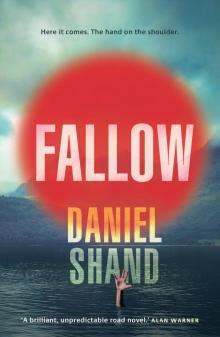

Fallow

Fallow Read online

Daniel Shand was born in Kirkcaldy in 1989 and currently lives in Edinburgh, where he is a PhD candidate at the University of Edinburgh and a Scottish literature tutor. His shorter work has been published in a number of magazines and he has performed at the Edinburgh International Book Festival. He won the University of Edinburgh Sloan Prize for fiction and the University of Dundee Creative Writing Award.

www.daniel-shand.com

@danshand

First published in Great Britain

Sandstone Press Ltd

Dochcarty Road

Dingwall

Ross-shire

IV15 9UG

Scotland

www.sandstonepress.com

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

Copyright (c) Daniel Shand 2016

Editor: Moira Forsyth

The moral right of Daniel Shand to be recognised as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Design and Patent Act, 1988. The publisher acknowledges support from Creative Scotland towards publication of this volume.

ISBN: 978-1-910985-34-2

ISBNe: 978-1-910985-35-9

Jacket design by Jason Anscombe of Raw Shock

Ebook compilation by Iolaire Typography, Newtonmore

For Ivy

Contents

Title Page

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

Acknowledgements

1

Something had been in the night and rubbish was strewn all across the grass. I hadn’t heard anything myself but there were crisp packets and beer cans and polystyrene trays scattered around the tent, our carrier bags torn open. We’d spotted some deer up in the hills a few days earlier but it could just as easily have been a fox or a badger or one of the other beasts that roamed around out there. I scanned the ground for human footprints and felt my blood go down when there were none to be found.

I pulled my head back inside the tent and wriggled into my jeans.

I must have disturbed Mikey. He mumbled something.

‘What’s that?’ I asked.

He unzipped the door to the sleeping area and stuck his head out, a mess of greasy hair and beard.

‘What’s going on?’ he asked.

‘Nothing’s going on. I’m just getting up.’

‘You don’t mind if I go back to bed?’

I told him to knock himself out and I crawled outside. The morning air nipped at my bare torso and I slid on dew as I skipped around, picking up the rubbish and stuffing it into a fresh bag. Once I’d tidied up I got the gas stove out from the tent and made myself some coffee. I sat on the groundsheet and rolled a fag while the coffee pot boiled.

A bird of prey swooped out from behind one of the mountains that flanked the meadow, flying in wide arcs, in perfect curves. I hoped it would spot some fluffy wee rodent down in the grass, maybe even whatever it was that ripped apart our rubbish bag. I wanted to see it dive towards the earth and snatch up its prey. It didn’t though. I kept my eye trained on it until it went behind the mountain again, and then the coffee pot was whistling so I poured some coffee out into my tin mug and lit the fag.

I relished this quiet time in the morning, before Mikey woke. These were the only moments, apart from when I went to town for supplies, that I had for myself. I’d sit and have my coffee and my fag and listen to Mikey snoring and the mad gurgle of the burn down the hill. There was a road beyond the burn that cars rarely used and a house halfway between us and town. We’d selected the site for its remoteness.

Mikey yawned and began to move around inside the tent. Here we go, I thought. He squeezed past me carrying his boots. Same thing every morning. He’d hop around on the wet grass in his yellowing Y-fronts, trying to squeeze into his boots without untying them, before giving up and throwing them down beside the tent.

I watched his routine and sipped my coffee. It tasted horrible.

‘Fuck it,’ he said, chucking the boots away. He ran his fingers through his long hair and scratched at his beard. ‘Morning then,’ he said.

‘How did you sleep?’ I asked, knowing fine well that he slept like a log, because I was the one who had to listen to his snoring.

‘Good,’ he said, stretching and squatting. ‘Well, not bad. Here, mind if I nick a cup?’

‘Fine.’

He squeezed past me to get his mug out from the tent. He had no qualms about pressing his bare flesh against mine. Personal space was not part of his understanding. I poured him some coffee and he stood facing the mountains with his free hand on his hip. He drank a mouthful and I waited for his grimace.

‘Paul,’ he said. ‘I don’t really like coffee.’

‘No,’ I said. ‘I know.’

‘Do you mind if I…’ he asked, miming pouring the cup away.

I shook my head. This was also part of his routine, trying my coffee and inevitably not enjoying it and being timid about throwing it out. That wasn’t every day, like the boots. More like every other day.

After I’d finished the rest of the pot we collected our towels from the guy ropes and traipsed down to the burn for a wash.

‘So,’ said Mikey. ‘What’s the plan for today?’

‘Same as always. I’ll go into town for a bit of food and a paper once we’ve cleaned up.’

‘Right,’ he said, dropping his head.

‘Don’t sulk, Mikey.’

We faced away from each other once we’d taken off our boots and jeans and pants. It was difficult to wash in the burn, because of the cold and the shallowness. You had to scoop up handfuls of water to rinse your hair and squat down to let the water wash your arse and balls. I winced at the coldness that was also a kind of hotness.

Once we were dried off and back into our trousers we turned to face each other. ‘Feels better,’ I said.

‘Yep.’

I spotted a car down on the road as we were walking back to the tent. It was one of those big four-wheel drives and it was parked in a passing place.

‘Here,’ I said, tapping Mikey’s arm to make him stop. ‘See that?’

He peered past me. ‘It’s a motor.’

I tried to make out who was inside, but it was too far off.

Mikey shook some of the wetness out his hair. ‘Reckon they can see us?’

‘I don’t know,’ I admitted. It was about half a mile down to the road, but there was a good chance they’d be able to make us out. Still, it would seem more suspicious if we stood there and watched it like that. ‘Let’s keep going,’ I said.

Up at the tent I did my best to dry my hair before fetching a shirt from inside. All my clothes were getting foul and I knew Mikey’s would be ten times worse than mine. At some point I’d have to make a special trip into town to use the laundrette.

‘Right,’ I told Mikey. ‘I’m going to head down now. You going to be all right?’

‘Aye,’ he said. He was hunched in the tent’s entrance, his head hidden beneath the towel. ‘Like you said, same as always.’

‘What do you say if someone comes?’

‘That we’re ramblers.’

‘Good man.’

I walked down the hill towards the road and was relieved to see the car had moved on. It was only an hour or so into town, the road taking me past the wee house and then right down the valley. Again, this was time I tried to enjoy. There was

the worry that some landowner or a group of hill walkers would chance upon Mikey and he’d panic and give them the wrong story, but I tried to ignore that.

What we called town was really just a village. There was a Spar and a pub and a butcher shop and all the other things you’d expect from a place like that. I kept my head down as I walked, never wanting to become a familiar face to the people there.

The butcher was a rancid man. He looked up at me and gave me one of his red-lipped smirks as I entered. He was obese and ginger and had streaks of blood up his forearms.

‘Hello,’ I said.

He winked. ‘Morning. What’ll it be?’

‘I’ll just take four…’

He interrupted. ‘Four sausages.’

‘Aye,’ I said. ‘Four sausages.’

He winked again. ‘Coming right up.’ There was a big basin behind him that he washed his hands in. I could see through the door to the back room, where his acolyte was hacking at a hanging carcass.

‘So,’ said the butcher, turning to me and plucking a piece of cling-film from the dispenser. ‘We’ve got Cumberland, we’ve got Lorne, we’ve got Lincolnshire, we’ve got ring.’

The back door creaked open and the boy emerged to gawk at me. His apron was soaked with blood.

I looked at all the sausages he’d named. ‘Just norm…’

‘Four normal sausages coming right up,’ said the butcher, smirking.

He scooped my order up in his cling-filmed hand and put it into a plastic bag. I had my money ready, the change gripped in my hand inside the pocket of my jeans. I knew exactly how much four normal sausages cost. My grip was so tight that the coins hurt my bones.

The butcher paused as he was handing the sausages over the counter. ‘Sorry,’ he said. ‘It’s just… Andrew and I were wondering...’

‘Yes?’

‘Well. You come in here nearly every morning and ask for four normal sausages.’

I was starting to sweat under my collar. I gripped hold of my change. ‘That’s right.’

He leaned over the counter, smirking, glancing back at the boy he called Andrew. ‘Only ever four sausages. For the past maybe two months.’

‘Aye. That’s true.’

He laughed. Andrew touched his bloodied apron. ‘Well. I mean. Why only four?’

‘I don’t understand. I only need four.’

‘What I mean is, what’s to stop you coming in half as often and buying eight sausages or so on? Stock up?’ He peered at me from under his orange eyebrows. ‘They would keep.’

I swallowed. I looked at the obese butcher, I looked at Andrew’s apron. ‘My fridge is broken. I’m saving up for another one.’

The butcher’s face fell. ‘Oh.’

‘Aye.’

‘That does make sense I suppose.’ He handed me the parcel of sausages and took the wet change from my hand and rung it up on the till. There was dried blood stuck to the cuticles of his fingers. ‘Me and Andrew were curious is all. Cheerio then.’

‘Right. Well. Cheerio.’

I kept walking until I was out of sight of the butcher shop, then I leaned again the wall of the Chinese and let my breath out. After a minute I ducked into the Spar to collect the rest of our supplies. Luckily they seemed to have a never-ending supply of teenage girls to employ; I never saw the same one twice.

I followed the road and then the burn out of town. I passed the wee house and noticed the car parked in the driveway for the first time. It was only the bloody four-wheel drive from before! I thought about sneaking into the garden to try and have a look inside, but getting caught was too big a risk.

Mikey was messing about outside the tent. I could see him hopping around from all the way down at the base of the hill. He didn’t notice me until I was right behind him. He was playing keepy-ups with a football.

‘What’re you doing?’ I asked.

Mikey flinched and turned, missing the ball. ‘Fuck Paul. You made me mess it up.’

‘Where did you get that?’

He pointed to the thickets and undergrowth that marked the edge of the meadow, leading to the mountain’s foot. ‘It was in the bushes there.’

‘Really?’

‘Aye.’

‘Did anyone come?’

He rolled the ball towards himself with his foot and kicked it into the air. ‘Nope.’

I said, ‘Good,’ and put the bags down. I found our stove and the frying pan and set up the sausages to fry. ‘When I was coming up, I went past the house further down the valley.’

‘Oh aye?’

‘Aye. The car from before was parked in the driveway. They must live there.’

‘Right.’

‘Doesn’t that worry you?’

He caught the football on top of his boot and held it in the air. ‘Why would it?’ he grunted.

‘Well, they seemed to be taking an awful interest, didn’t they?’

‘I suppose.’

‘I hope we won’t have to move on again,’ I said, pushing the sausages around with a lolly stick. I kept forgetting to pick up some tongs or a spatula from town.

We’d been up in the valley for a month or two, as the butcher had said. Before that we’d camped out by a loch but fishermen started to show up when the season changed, forcing us to pack up and move on. Before the loch we’d been in fields behind the town where we lived, miles and miles from this little sanctuary under the mountain.

I dished out the sausages onto two cardboard plates. ‘Leave the ball for now,’ I told Mikey, handing him his.

He sat cross-legged on the grass, blowing on his sausages. ‘Here, Paul,’ he said. ‘What’s a sausage made out of anyway?’

‘That’ll be pig in that one, but you get all sorts.’

‘Right. So it’s like chops then. Pork chops.’

‘Kind of. They put all the bits of the pig no one wants to eat in sausages.’

‘Why’re they so nice then?’ He’d already wolfed down both of his and was huffing on the steaming morsels still in his mouth.

‘I don’t know. They just are.’

Mikey eyed my one remaining sausage. ‘Are you going to finish yours?’

‘We’ll split it,’ I said, cutting it in half with a plastic knife and giving Mikey the bigger half.

‘Cheers Paul.’

I put the stove back in the tent once it was cool and threw away the plates. I dug the paper out from the Spar bag. ‘I’m going to check this,’ I told him. ‘You wanting to look with me?’

He shook his head. ‘Nah. It’s too nasty. I’m going to stick at the football.’

I lay down in the tent’s opening and leafed through the paper. I could hear Mikey kicking the ball from somewhere behind the pages. For the first few weeks after we’d left, Mikey had invariably been on the first page. He’d slowly descended through the paper over time and I was waiting for the day when he wasn’t featured at all. Maybe then we could go back.

I was nearly at the sport section when I found him. ‘Fuck,’ I said. They’d printed a recent picture with the article. He had his long hair in this one, and his beard. For a long time it was the police mug shot they used, which wasn’t so bad because the frog-eyed boy of thirteen didn’t look much like the fully-grown Mikey. I didn’t know if there’d been some court ruling that meant they could publish a new picture or perhaps they’d just stopped giving a shit.

I heard Mikey moan from behind my paper.

‘Gone in the burn?’ I called.

‘Aye,’ he said.

‘Listen mate,’ I said, laying the paper down on my chest. ‘We’re going to have to do it. They’ve got a new photo here. Your hair’s all long in it.’

He put his hands on his head. ‘We can’t, Paul. It’s the perfect length.’

‘We’ll have to, mate.’

His eyes started to redden. ‘Maybe we could just wait and see what happens…’

‘Fucken wait and see?’ I said. ‘How long you wanting to be stuck out here?’

> ‘It’s just…’

‘Never mind it’s just. Get your T-shirt off. Now.’

I found the scissors in my bag of supplies from the shop. I made Mikey sit on the grass and I kneeled behind him. I cut his hair right down and he cried the whole time. I turned him around, wiped the loose hairs from his face and cut his beard down too. I gave him the cheap pair of sunglasses I’d picked up from the rack in Spar.

‘Give them a try,’ I said.

He put the glasses on and had a look in the superfluous shaving mirror we carried around. His face crumpled. ‘I look like fucken… fucken Lou Reed.’

‘Don’t sulk. It had to be done.’

Mikey fished his ball out from the burn and I went back to the paper. We killed the afternoon like that. He practised his keepy-ups and I read every single article and completed every single puzzle. Once I was finished we played the football together. We used the gas stove and the frying pan as goalposts and I played goal. As Mikey was making shots past me he looked the happiest I’d seen him in some time, despite the haircut.

‘There’s this butcher in town,’ I told him as I caught a lob he’d tried to put past my head.

‘Oh aye?’

‘Aye. Asking questions.’ I threw the ball back.

Mikey caught it on his stomach. ‘What sort of questions?’

‘Asking questions like, how come I go in there so often and that.’

Mikey didn’t answer me, just tried to send the ball low across the ground. It collided with the stove.

‘Doesn’t that worry you?’ I asked.

‘He’s probably just taking an interest.’

‘I think he knows. Might recognise me. Maybe the family resemblance or something.’

‘How could he know?’

‘He handles meat for a living Mikey. He knows who’s lying.’

We got bored of the football soon enough. I tried to lie on the grass and have a sleep, but Mikey was too restless. He rolled around on the ground, pushing his head into the earth with frustration. ‘I’m so bored,’ he said. ‘Bored.’

‘I know. I am too.’

‘But you don’t get it. I’m really fucken bored.’

Fallow

Fallow